The tech side of medicine

Whether you need to develop a vaccine in record time or detect a pathogen in a patient sample, these three TechOffers have got you covered.

Like a police squad on patrol, our immune system is constantly on guard against disease-causing microorganisms. But sometimes, bacteria, viruses and fungi can slip past or overwhelm the body’s defences, resulting in unpleasant symptoms. When that happens, it is important to identify the offending pathogen so that the appropriate treatment can be administered, and health can be restored.

Over the years, doctors have increasingly relied on technology to help them precisely diagnose infections. Rather than rely on qualitative assessments of a patient’s condition, such as observing for redness or swelling, healthcare professionals now have access to a range of diagnostic tools that allow them to measure specific compounds associated with disease. The sensitivity of these tools has also improved tremendously.

Even with the help of new diagnostic tools, the battle lines between doctors and infectious diseases are constantly shifting. In the past decade alone, we have seen the appearance of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus, new avian flu viruses and numerous drug-resistant strains of bacteria. Therefore, not only must detection methods keep up, the development of new vaccines and treatments must also be accelerated.

In this month’s TechOffers, we highlight three tools in the biomedical arsenal that are helping researchers and clinicians stay ahead in the arms race with disease-causing microbes.

Prevention is better than cure

One of the best ways to prevent illness is to vaccinate against the offending microorganism. A vaccine works by priming the immune system against a specific pathogen. Think of this as a tip-off by an informant (the vaccine), allowing the police (the immune system) to spring an ambush on thieves trying to break into a store (the pathogen).

When it comes to vaccine development, there are two main approaches: an inactivated vaccine consisting of a pathogen that has been killed by heat or chemicals; or a live-attenuated vaccine (LAV) consisting of a weakened but living pathogen. LAVs generally perform better than inactivated vaccines. Many viral diseases, including chickenpox, measles and yellow fever are prevented by LAVs.

Conventionally, LAVs are discovered rather than developed—that is, weakened strains are found serendipitously in animals or through cell culture. This is poor assurance of a suitable vaccine in the event of an infectious disease outbreak. To improve the reliability of LAV development, a method to rapidly generate attenuated strains by tinkering with the DNA of pathogens has since been developed. This approach reduces the time taken to develop a LAV to about ten weeks, as opposed to traditional methods that require years.

Shedding light on disease

Vaccines are most effective in healthy individuals. But if infection has already occurred, the fight then moves into a different phase—detection. There are several criteria to be met when developing a detection kit for disease-causing microorganisms. Most crucially, it should be sensitive enough to pick out a specific type of infectious microbe. Ideally, the method should be fast (as some disease progress quickly), portable to allow for diagnosis in field settings, as well as inexpensive so that people can afford to get themselves tested.

Fulfilling these criteria is an optical-based nano biosensor for the rapid detection of the flu virus. The detection system comprises two types of nanoparticles which allow concentrations of flu virus DNA as low as 300 femtomolar to be detected. Under near-infrared light, the system gives off a green fluorescence in the presence of flu virus DNA. Compared to visible light which is typically used in optical-based detection systems, near-infrared light is less damaging to biological samples, which increases the accuracy of readouts.

Moreover, because diode lasers that produce near-infrared light are inexpensive, widely available and compact, this nano biosensor is cheaper to manufacture and portable. The nanoparticles used can also be further modified to suit other applications, such as water quality monitoring or temperature sensing.

No labels? No problem

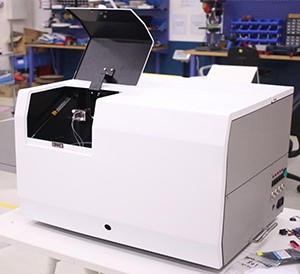

The preparation of samples for analysis is often time-consuming and requires the use of labels, such as fluorescent probes. This customisable sensor platform for highly specific analyte detection, however, is label-free, thereby sidestepping the need for complex sample preparation protocols.

The system includes a functionalised gold sensor chip onto which a sample is applied. An optical signal is then generated, which can be used to identify a specific compound in the sample, as well as determine the concentration of said compound in real time.

The highly sensitive chip can produce a readout within minutes, thereby making it possible to detect and quantify biomolecules—whether they be virus particles, bacteria or toxins—under time-sensitive circumstances. Designed as a compact benchtop system, this technology could be deployed to enhance food safety, perform medical diagnostics and carry out real-time monitoring of air and water pollution.